Eurasia note #70 - Mutually Assured Destruction & Environmental Agenda

Threat of nuclear annihilation makes a timely reappearance

Why civil defence was dominant for one generation and why it went away

If mutually-assured destruction kept peace, how so no longer necessary?

Fading of MAD signaled not the end of superpower rivalry but its re-emergence

It takes a comedian Jimmy Dore to warn the U.S. is provoking war with China

Having baited the Russian bear, Anglo-Americans are needling the dragon

The globalists need China as a foil to deceive their own people

Oiler-bankers are locked in their history of commodity piracy and slavery

JFK spoke of “making the world safe for diversity” of coexistence

What is today’s unspoken message?

Related:

Oppenheimer Film Pulls Focus On Nuclear Annihilation - Mutually Assured Destruction makes a belated come back (Jul 21, 2023)

Timeless Voice Bids Us 'Come And See' - A film with lessons from Byelorussia to Gaza (Jan 14, 2024)

Oppenheimer Film Pulls Focus On Nuclear Annihilation - Mutually Assured Destruction makes a belated come back (Jul 21, 2023)

German Film That Foresaw The Plandemic - Peter Fleischmann captured medical tyranny in a Seventies blend of thriller and satire (Mar 23, 2022)

Mutually Assured Destruction And The Environmental Agenda - Threat of nuclear annihilation makes a timely reappearance (Feb 13, 2023)

Sci-Fi Icon Saw Plague Heist Coming 60 Yrs Ago - Philip K Dick on the psychology behind government selling 'protection' (Feb 03, 2022)

(4,700 words or 22 minutes of your time).

Tbilisi, Feb 13, 2023

Canterbury, Kent, England, 1970-something

Modestly intact after 30 years, in their neat asbestos rows, the prefab homes stand silent and empty in their ungated community at the end of our street. Built as temporary, modular homes for those who’d been “bombed out” in the London Blitz, no one wants to live in them now.

At the entrance to the alley beside our school, the tank traps loom timeless and massive to our childish frames, too tall to climb; pyramids of cement and aggregate, monuments to inhumanity.

The hill that overlooks the city hides the air-raid shelters whose filled-in entrance is betrayed by the slippage of its reinforced-concrete roof. The war had ended 15 years before we friends were born but now we are ten. We wriggle, lamps ablaze, into the damp and dark of war games.

In these days of the early 1970s the realm of our knowledge is framed by our circle of friends and relations. What we hear of war comes though the stories told by uncles who adapt factories to wartime production; the geography teacher who is a naval commander. We see lines in the face of our grandmother, who tells with sardonic wit how she escapes the London Blitz only to move to the Kentish countryside above which bombers, turning tail, unload their payloads. What we taste of war greases the school canteen where powdered egg is rehydrated and scrambled, SPAM fritters are a staple, and where suet pudding remains the pinnacle of luxury.

The unimaginable future will one day unleash a world of amorphous voices beckoning through the Internet; exchanges and connections with those whom we may never meet. For now, when we speak to father abroad, we call the operator to book a call, and when we reach him we pause to allow time for the words to travel down the line, lest we talk across each other.

The expansion of our circle, the blending of friend and acquaintance, the rerouting of conversation, has yet to occur. The connection, from the exchange to our person, is still short and direct.

I call my grandparents only to tell them I’ll visit. Then I walk, 45 minutes at a brisk pace, down the hill, through the Westgate and the city centre, past the bombed church where the master of Elizabethan theatre, Christopher Marlowe, was baptized — only the bell tower stands — and in the direction of Dover where I’ll receive the kind of greeting that fewer children than deserve nowadays receive.

Fifteen minute cities: take a hike!

A bleak house

Information flows more freely, or so we are told. Is that so? Does the world just described sound under-informed? One might say it was small but deep, as opposed perhaps to today’s world that is broad and shallow.

Information is not knowledge, as the cultural historian Theodore Roszak noted, for knowledge is explored through ideas. And without knowledge, he said, one has no chance of wisdom — explored in the post, Information Drives the Muscles not the Brain.

Information is suppressed far more easily than knowledge. Information can be turned off like a spigot. It takes decades to constrain knowledge — for knowledge is like the capacity of a pipe — the malevolent strategy is the narrowing of our thinking pipes; what is crudely called dumbing down, as recently deceased Charlotte Iserbyt named it.

To go further, information may be hoarded: access clearly is not equal but nor is the knowledge necessary to make use of information available equally to all. Here we meet that curious word equity: the apportioning of access, rather than equality which is the equal right of access.

Consider the nature of knowledge, versus information. The suppression of information about early treatments for the coronavirus was so obvious it is clear there was an agenda of which we have knowledge — the only question is which agenda.

The motivation of hate speech laws is revealed by Facebook which allows hate so long as it is directed currently against Russians. Who knows who tomorrow’s “vermin” may be.

Nuclear winter

There is a part of the culture of the 1970s that has been absent for many decades — until recent months. The impact of nuclear war information campaigns loomed large in the world of a teenager, as the folk memory of World War Two gave way as the 1970s progressed, to the Cold War.

Those whose school days embraced long hot summers (at least in the UK) recall “protect and survive,” a civil defence programme that ran for six years from 1974.

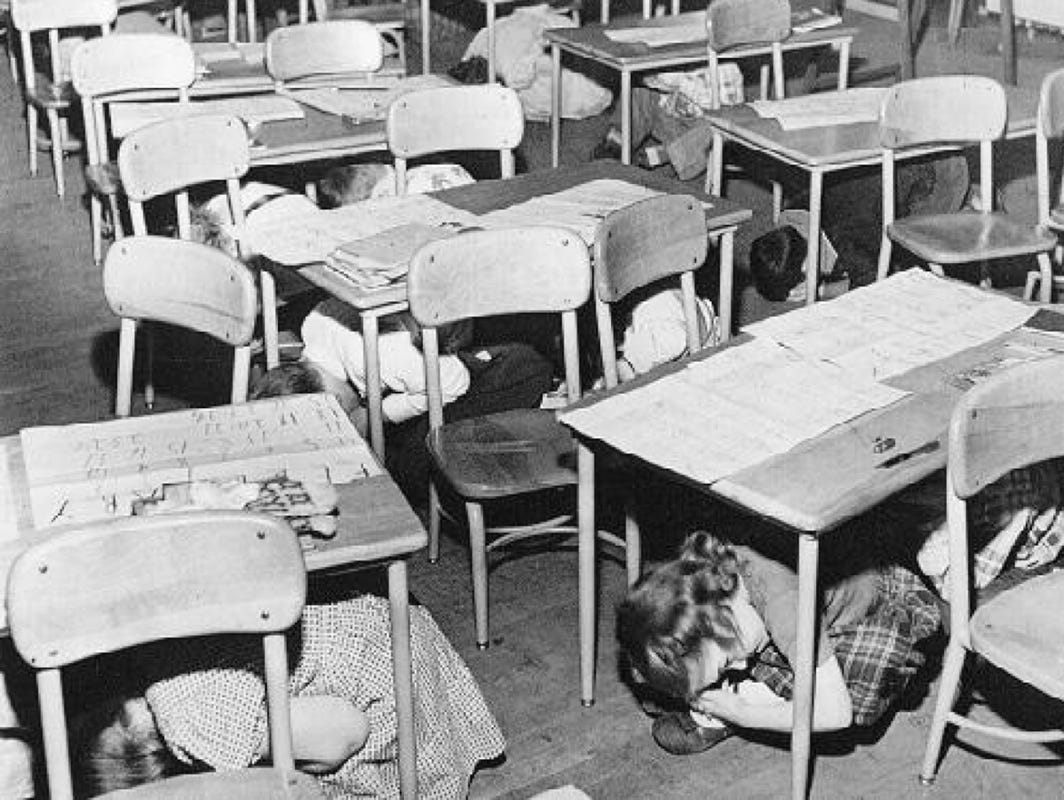

It is not the government leaflets nor the laughable advice to hide under your desk that survives in the memory. It is not the shifting hands of the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. Rather it is the documentary films of those days, that burned the threat of carbonized annihilation into our minds.

The most powerful was Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1965). Although suppressed at the time by the BBC and the UK government, it is prescient on many counts.

In one scene, set in the south-eastern English coastal county of Kent, people are told that the time from warning to impact might be little more than two minutes.

In this scenario, the Soviet Union’s nuclear weapons are vulnerable to destruction thus imposing the logic to launch them in the early stages of a confrontation.

The contagion agenda

Schools no longer teach students about nuclear war, neither through public service films nor documentaries. Hollywood and made-for-television series are obsessed with contagion and zombies.

Deadly viruses, especially the man-made, escaped from lab variety, have long been a staple of cultural programming. Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal from 1957 is a class above modern narrative, pushing the Black Death of the 1300s into the background of a Faustian battle with archetypal forces.

It is a rather more elegant commentary on the failings of modern life than that satire on consumerism, Dawn Of The Dead (1978).

Others are more obvious cultural programming like 12 Monkeys (1995) in which the protagonist time-travels from 2030 to the 1990s to discover the origins of a man-made virus that killed billions of human beings.

When not snorting hits of dopamine from TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram, the younger half of the population is genned up on the supposed existential threat of zombies and climate change. This may seem more tangible than aliens and asteroid impacts for the simple reason that zombies are our dark mirror: the zombie is the lifeless body reanimated without the soul; the threat of life in limbo that forms part of most religions and is a nightmare of sleepless night even to the adamant atheist.

We must separate the two: zombies are a perennial, if not eternal, hardened to the frost or lava of a restless climate. If we might save our soul from the damnation of a zombie, we are as ants in the face of the climate. Yet with which do we contend: why, we’ll take on the climate, silly! Like Icarus, who should you choose to defy if not the Sun?

The threat of nuclear war is something that we humans can contest. Instead we bury the narrative and presume to control with a fine dial that which we barely comprehend, and by which we are outclassed — we choose to duel with giants.

Reaction time

Prof Steven Starr points out that table top war exercises always escalated into nuclear war. Today, the decision-space is more narrow than ever: hypersonic missiles travel at mach 9, which is 112 miles per minute, and Washington DC is less than 100 miles from the Atlantic coast.

In the case of a submarine or frigate-launched missile, detecting the launch, reporting to command, presidential approval and launch of Minute Men cannot happen in less than five or six minutes. “That creates the pressure to have a pre-emptive strike… use it or lose it,” Starr told Geopolitics and Empire podcast. [1]

The public is shielded from unexpected consequences and accidents. Since 1985 the U.S. has withheld information about false alarms and near misses. In that year NORAD accidentally broadcast a training video on the main screens showing an incoming ballistic missile attack,

We were told in the 1970s and 80s that nuclear weapons guaranteed peace. The theory of mutually assured destruction (MAD) meant it was in no-one’s interest to launch a mass ballistic attack on another superpower.

Nuclear narrative

Two decades after The War Game the BBC, in 1984, broadcast Threads, a documentary series about effect a nuclear attack would have on civilian life, focusing on the British industrial city of Sheffield.

What took the BBC so long, one might ask: domestic politics and the growing force of environmental studies; the establishment’s need to undermine anti-nuclear protesters, while acknowledging studies of the impact of a nuclear winter in the early 1980s.

The astrophysicist Carl Sagan warned that smoke and particulates following a nuclear explosion could obstruct the sun, causing greater loss of life than the initial blast and radioactive fallout which would “kill ‘only’ hundreds of millions of people.”

Today environmentalists tout the advantage of obstructing the sun. Transhumanists have little time for humanity as most people know it. Is it a stretch to conjecture that some might see nuclear obliteration eliding with their aims?

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) was a growing force in British politics, and a powerful bed of support for then leader of the UK Labour Party (1980-83), Michael Foot. The British establishment was fiercely opposed to Foot.

Although Labour was to lose the 1983 general election (with its lowest share of the vote since 1918, and its fewest MPs since 1945) the party had just two years earlier been riding high in the opinion polls against prime minister Margaret Thatcher. In Greater London Ken Livingstone had led a massively popular revolt against the Poll Tax and the privatisation of public services.

British and U.S. intelligence had been in a state of high paranoia since Harold Wilson had become Labour leader prime minister in 1964-70 and again 1974-76. There was talk from all sides of the political spectrum of spies ready to stage a coup against Wilson. [2]

Having sidelined CND, the British establishment took ownership of the narrative, though the climactic devastation would soon be overwhelmed by the environmental movement. Indeed, warnings of nuclear winter were soon dismissed as the modeling of “scientific Cassandras.” [3]

Fifteen years after MAD disappeared and CND faded from the public screens, the growing field of climate studies has reanimated the discussion of the consequences of smoke from nuclear firestorms flowing high into the atmosphere, blotting out the sun for longer than initially modeled.

A report by International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War suggested a decade ago that two billion people could face “nuclear famine,” but there has been little further research into the collapse of public heath systems, clean water supply, the impact of radiation on cancers and the ecosystem, plants and animals, or the impact on a digital society of electromagnetic pulse.

No mistake

You might think that the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1989-1991 removed the threat of war. According to declassified U.S. documents American officials gave repeated assurances that NATO would not expand to the east. [4]

And so the eight and final leader of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, who died just recently in Aug 2022, agreed to abandon the Warsaw Pact, the military alliance of Eastern Europe.

The actions, rather than words, of Western leaders tells a different story.

In 2002 the U.S. withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in place since 1972, citing the need to counter a growing nuclear threat from Iran. The ABM treaty was intended to reduce the incentive to build offensive missiles, by agreeing to limit defensive batteries. President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, or Star Wars, proposal (though it never came to fruition) helped undermine the ABM treaty.

In 2019 the U.S. pulled out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty governing land-based missiles. The pretext was Russian non-compliance but the U.S. also claimed the need to build up its weaponry against China, which was not a signatory to the treaty.

The same year the U.S. abrogated the 2002 Open Skies Treaty which provided for mutual aerial oversight of weaponry.

Russia’s response at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 led to the development of hypersonic missiles.

Western government wished to avoid a narrative that contradicted their actions. The U.S. was determined to pull out of threat reduction treaties that had helped secure an end to the Cold War. The pretext was the emergence as powers of China and Iran.

The Pentagon was to use the pretext of September 11th, 2001, to launch seven wars, according to retired U.S. general Wesley Clark: “beginning with Iraq, then Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and finishing off with Iran.”

So the omerta on public discussion of mutually assured destruction coincided not with the end of superpower rivalry but its re-emergence. One is tempted to wonder: does the establishment only talk about mutually assured destruction when it discounts the threat — and when it feels the threat real, takes refuge in its negation?

Magical thinking

In the eyes of neoconservatives, MAD had not so prevented great power conflict but frozen it. By preventing the “rolling back of the power and influence of a dangerously expansionist and totalitarian Soviet Union” it prolongued the life of “an evil empire.” [5]

Now the state media gives prominence to voices that openly discuss winning a nuclear war.

“What we see today is magical thinking in so many areas, whether it is military or economic policy,” says Prof Steven Starr.

Chinese newspaper Global Times observes that the U.S. is a country out of time — not in the sense of a stopwatch but an era. [6]

The unwritten takeaway is that the U.S. is trapped in the commodity economy of its origin, “the system design at the initial stage of its founding was based on an agricultural society. Now that the world has already entered the information era beyond the industrial age, this institutional system must undergo major changes.”

This makes for a cogent argument. The U.S. economy rose to pre-eminence under farming and the extractive industries like oil and its system is built around them. This is the territory of its dominant families: the oiler-bankers, the Rockefellers and Rothschilds; the old European royal families, their financier enablers and their aristocratic hangers on.

China, in contrast, was forced to wait for historical and technological developments to unleash the potential where, “Even countries that are lacking in natural resources have achieved development by investing in and tapping human resources.”

The Anglo-American West responded by inverting the meaning of free trade, of a rules-based international order, to mean only that which serves the oiler-bankers is worth of the name. Even their precious usury has been turned from a source of credit for growth into an extractive industry whereby successive booms and busts are required for the banker-croupier to sweep the collateral from wreckage of lost fortunes into his apron.

The Anglo-American oiler-bankers are locked in the mindset of their origins, that of commodity resource piracy, not to mention human slaving.

Bouffant globalists

Who cannot notice globalist hair: big, floppy, glossy, bobbing to each other in some secret, unspoken code; does it speak of rejuvenation, a transhumanist symbol, is it what the puppeteers consider the smiley face of fascism, or do they just share the same Turkish transplant clinic?

Even Russell Brand has noticed and poked fun at the distraction of “lovely hair.” From the Bee Gees, to Barry Manilow, to Richard Branson, Thierry Breton or Ursula von der Leyen it is hard to miss that the hair is talking, just as surely as the antiquated pubes of old.

Perhaps a big barnet, a bulging hair net speaks to some primeval sense, prompting admiration or humility before the lion’s mane. Or is it a token of our infantilized world in which politicians play the ever 20-something? The legislature as Friends or Cheers?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Moneycircus to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.