A Futurist And A Luddite Walk Into A Bar

The second of three articles on the modern incarnation of fascism

Part One saw fascism as corporative state, Mussolini’s co-option of the guild system.

We heard the case for the mechanisms of fascism as separate from spirit or intent.

See Moneycircus, May 27, 2022 — Philanthropy Is The Third Pillar Of Fascism

This article questions that distinction: technology embeds fascism as potential.

It denies privacy; cancels the individual; puts inclusion in the hands of the powerful.

If Bolsheviks turned the world upside down, fascists turned the person inside out.

(2,200 words or about 11 minutes’ read.)

Firstly fascism says the individual is allowed no existence outside the community, to which you must affirm your conformity. “Nothing outside the state,” declared Benito Mussolini.

The second dictum is that the powerful in society decide who belongs, and who is excluded, according to the main ideologue of the Nazi party Carl Schmitt.

Jun 15, 2022

The Futurist debating team will beat the Luddites; you know it. But they’d agree on one thing: life imitates technology.

Elon Musk has sparked a series of articles comparing him with the Italian Futurist poet Filippo Marinetti and the political trajectory of technology.

No, Twitter isn’t poetry despite our best attempts. Nor does technology possess logic, though that may change with artificial intelligence. It does, however, have its ideology.

Marinetti’s The Futurist Manifesto (1909) was harnessed by Benito Mussolini (who knew the value of propaganda because Benito himself was a propagandist in the employ of Britain’s MI5 who used him to boost support for Italy to stay in WWI — see below). [1]

The poet’s language makes you wonder if Marinetti wasn’t also in the employ of the British:

“We want to glorify war — the only hygiene for the world — militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.”

The racing driver’s talk of disruption, opening the door to progress by any means necessary — what his associates called “a church of speed and violence” — is not so far from today. Capitalism thrives on chaos, as a friend says, because the world is inherently chaotic, and an economic system that can deal with that elegantly, even thriving on it, is advantageous.

Nonetheless you feel the vibration as Marinetti opens the throttle on a dangerous corner, heading for an unsure destination. [2]

In that age of poets as “the unacknowledged legislators of the world” there were muses more profound who also played a pivotal role: Vladimir Mayakovsky whose use of political language was arguably more influential than George Orwell’s analysis; and Osip Mandelstam who sought to strip away the camouflage of euphemism and would pay with his life.

Ludd’s modernists

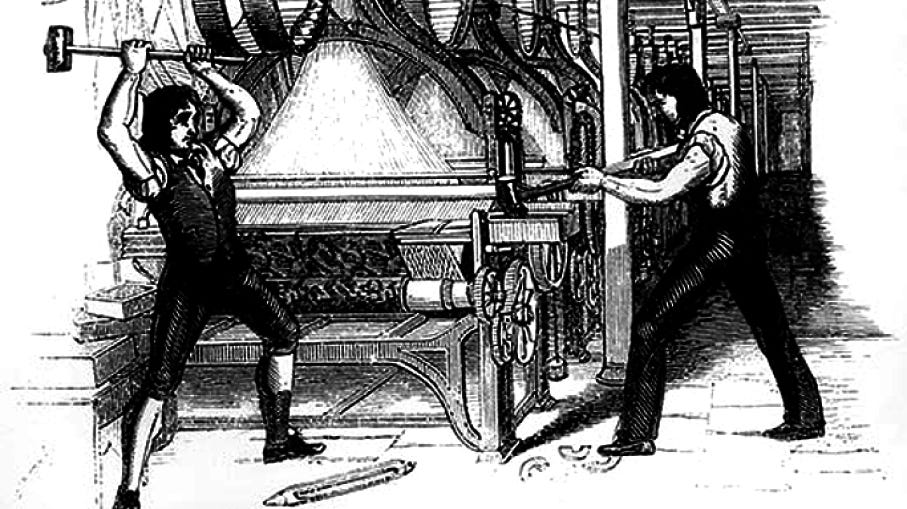

The Luddites were high-tech, working on cutting-edge technology: if they’d been peasants you would not know their fate. They were, the British historian Eric Hobsbawm said, the aristocracy of the working class; the successors of the guilds, the beneficiaries of a system that protected and encouraged specialist skills.

Suddenly they were presented with machines that could do their job more efficiently, and they didn’t say no: they simply questioned the appliance of science and their share of the resulting profit.

The Luddites asked for a stake in the surplus that flowed from greater productivity as they operated upgraded technology. They faced the same dilemma we all do today: improvements and efficiencies can make the worker’s life easier or harder.

Marinetti was wrong. Mayakovsky was right:

“This is the first day of the workers’ deluge. We come to the aid of the muddled-up world.”

Like the World Economic Forum and its pint-sized guru Yuval Harari, the British establishment could not manage or finesse those discomfited by this technological advance — and decided to eliminate them instead.

Parliament passed the Frame Breaking Act, executed up to 70 Luddites and transported the rest to Australia. Lord Byron was one of the lone voices among Britain’s ruling class to speak out, linking the distress of the workers to the disruption of trade by war.

Here's Lord Byron just over 200 years ago on the Luddites, whose behaviour he ascribed to the effect of 18 years of conflict, taxation and hardship, then followed by a technological update that reduced their income and, only then, prompted their protest: to which the government responded with a Bill for capital punishment:

“And what are your remedies? After months of inaction, and months of action worse than inactivity, at length comes forth the grand specific, the never-failing nostrum of all state-physicians, from the days of Draco to the present time.

“After feeling the pulse and shaking the head over the patient, prescribing the usual course of warm water and bleeding — the warm water of your mawkish police, and the lancets of your military — these convulsions must terminate in death, the sure consummation of the prescriptions of all political Sangrados.

“Setting aside the palpable injustice and the certain inefficiency of the bill, are there not capital punishments sufficient on your statutes? Is there not blood enough upon your penal code! that more must be poured forth to ascend to heaven and testify against you?” [3]

Byron could have been speaking today: the state masquerading as doctor, the official-executioner, the medical tyranny, bureau-psychologist-psychopath blood lecher.

Technology has an impact beyond jobs or products, against our integrity as individuals, with dire consequences for society and the political order.

Those weavers saw the value of their industry and took responsibility for their product. If machines lowered quality it devalued their individual worth and made a mockery of their skill.

A quality product that would sell at a good price, and last, would mean their own labour, their personal worth, was sustainable. The very opposite of, “you’ll own nothing and you’ll be happy.”

They saw mutual bargaining power as essential to their survival as individuals. Their collective action was against machines that eliminated the personal and distinctive, that left no route for the private, for their spirit to find an expression in output.

The owners dismissed the Luddites as wreckers but secretly shared their concerns and bought the hand-made furnishings of the Arts and Crafts movement, acknowledging the decline they had forced on the quality of goods produced in their own factories. [4]

Now the media splutters about the greater good, while the owners use profits to indulge their narcissistic selves like never before: $10 million for a four-minute flight near Space.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Moneycircus to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.