'Philanthropy' Is The Third Pillar Of Fascism

Governments seek unlawful objectives using charities and corporations as conduits

The first of three articles on the economic aspects of fascism:

Governments are using charities or non-profits as the third leg of a corporate state.

Money routed via NGOs helps corporations expand their role in society.

Achieving Mussolini’s vision of “nothing outside the state.”

WHO Pandemic Treaty is an example of creeping social and medical regimentation.

Media obscures definition of fascism, leaving most people unaware of our peril.

There’s “nothing to see” all around us: from Azov symbols to eugenics.

In the 1930s the U.S. borrowed elements of Mussolini’s corporatist economic system.

History cautions against using the mechanisms of fascism, lest some adopt its spirit.

Related:

Globalism, Socialism, Fascism, Feudalism (Part 1) (Sep 19, 2022)

Supra-National Socialism And Revolutionary Virtue — diversity, equity and inclusion ( Aug 3, 2023)

Science, Ideology & Supremacism - Modern technologies have roots in ancient theories (Aug 12, 2022)

When The Great Reset Is Complete — A future retrospective (Nov 23, 2021)

Guildsmen Trap Us in the Middle Ages: Rivals for Power

(2,800 words or about 13 minutes’ read)

May 27, 2022

Imagine yourself in 1934 just before all hell breaks loose. Suppose you already had a gloomy prescience of what would happen over the next decade because you had seen the rearmament and nationalism was just a continuation of WW1.

If you could travel back, from 1934 to about 1910 — not to change history (no-one would listen to you; they'd think you're mad) — you would nevertheless be able to spot the trajectory, even if it made you sick to the depths of your soul.

We’re in luck, because we have an article written in 1934, but more on that in a moment.

Fascism was an aberrant, 20th Century social experiment, defeated, or so we were taught. Somehow it was never defined: in recent years the label became a blunt insult. In the past week the Yale historian Timothy Snyder — whose “Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin,” is a must-read — further muddies the water.

In his article “Russia Is Fascist” Snyder confuses the outward appendages of fascism — violence, defining enemies, appealing to a national golden age, and vague parallels like a “cult around a single leader” — with the nexus of fascist power that is the combination of the state, professional organisations and corporations. [1]

We have to agree with Snyder, writing in The New York Times, that “fascists calling other people ‘fascists’ is fascism taken to its illogical extreme as a cult of unreason,” but he’s not helping. What ever you think of Russia’s behaviour — and Ukraine’s before the invasion — there is a bigger elephant in the room.

During Event Covid, the wealthiest owners told us they would reshape society. They used their control of the privately-owned central banks to buy the compliance of functionaries, and silence the media, to subvert the economic and political system.

This week they are busy in Switzerland weaving together seemingly different projects, like the braided locks of a Swiss maid.

Read their own words: it is not about health, it is an opportunity for a Great Reset. The question is what will be that economic system. The flags are everywhere but many people mistake their colour.

Definitions matter

Why should we mind if corporations and professions ally with government to take care of us; what’s the problem?

Should we be suspicious that corporate-owned media has been obscuring the creep of fascism for years? Google even removed the primary characteristic, “severe economic and social regimentation,” from its definition. [2]

What matters is motive — precisely the criteria that the corporate-owned press does not want you to consider: that business interests should want greater social control.

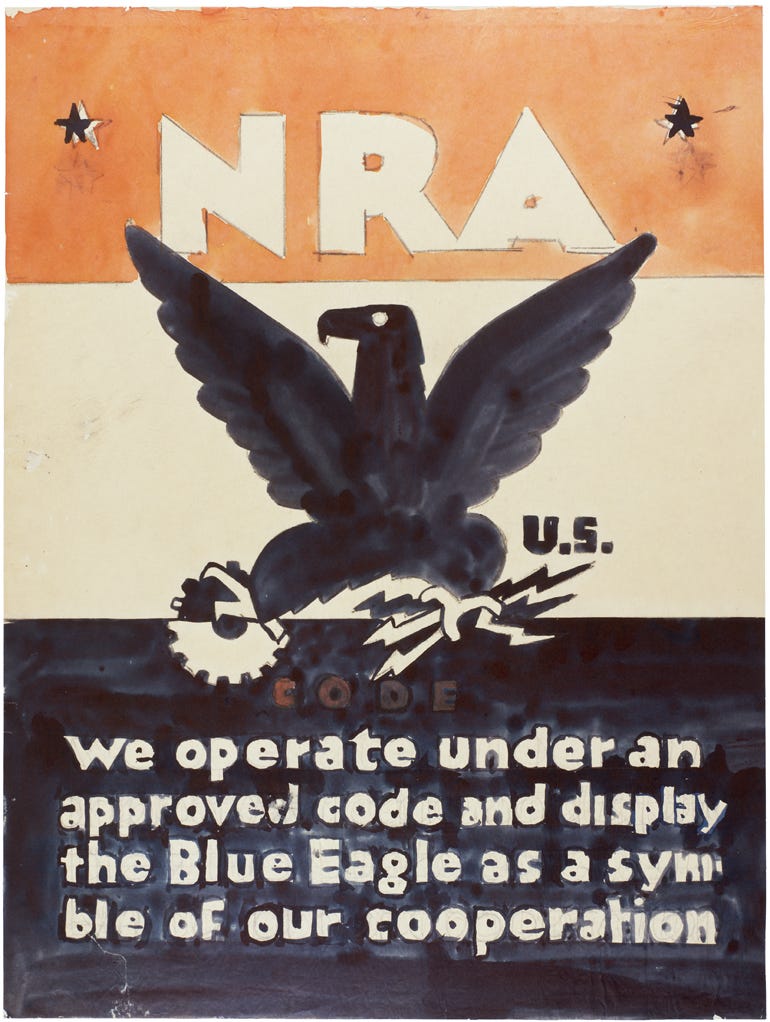

During the Great Depression president Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 borrowed many of the economic techniques of Benito Mussolini’s fascist economy in Italy. The Act created the National Recovery Administration which brought leaders of each industry together to create “codes,” including pricing and production mandates, under which they would limit competition and thereby increase purchasing power.

A Progressive writer, Roger Shaw, acknowledged the inspiration for the New Deal and set out to show that it was fascist merely in mechanics, but not applied to fascist ends.

Writing in the North American Review in 1934, Shaw gives us a perspective at the time when Mussolini was well established, Hitler had just taken power, and the Bolsheviks were less than 20 years into their rule. The United States had just suffered an unprecedented financial shock, which people called a crisis of capitalism just like they’re saying today. President Roosevelt had unveiled the New Deal and the National Recovery Administration. [3]

Shaw’s on-the-spot analysis is highly instructive and serves as a warning to us today — because he may not have been right. It is far from certain that one can separate a fascist economic structure from the social realities of fascism; nor the power which it gives the owners, from their desire to use it. (In 1935, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously declared the NRA law to be unconstitutional, ruling that it infringed the separation of powers under the United States Constitution.)

What this article aims to show is that fascism may not begin with corporations taking over the state, but there comes a point where the owners of those corporations seek total social control.

Guilds as oligarchy

Corporations and corporatism are related but different. Mussolini used the Italian word corporazione, which means not commercial corporation but guild in which workers and companies are grouped by trade or industry— a “corporative system in which divergent interests are coordinated and harmonised in the unity of the State.” [4]

Far from minimizing the role of business interests in the fascist state, however, the corporative system aggrandized the role of employers, giving them responsibilities in other spheres of human life. In fascism corporations answer to social and ideological imperatives, taking care of their workers’ health and leisure activities, even their political instruction.

Workers join a fascist trades union — “national syndicalism” — in which they must submit to management. Like the guilds they control the human and spiritual life of their apprentices, captured in Mussolini’s dictum: “nothing outside the state.”

“The word universitas originally meant an incorporated guild. These were some of the earliest corporations and, as such, were not entitled to own property nor to have permanent financial endowments as did the church. Their only power was to award degrees which bestowed upon the recipient a position in society. That was to prove unexpectedly influential.

“We see in the present moment the sidelining of legislatures populated by our equivalent of the bishops and gentry and the seizure of power by the incorporated guilds. In their modern guise they comprise elements of several institutions: the corporations, unions, secret societies, the professional organizations and the ever present puppeteers, the oligarchs and their tax-exempt foundations.”

See Moneycircus, Jun 2021 — Guildsmen Trap Us in the Middle Ages: Rivals for Power, Part One

Mussolini’s aim was to solve the problems of capitalism and poverty, recognizing “the real needs which gave rise to socialism” while maintaining private property.

We hear similar words today from the bank and owner class. Italy had its Council Of Corporations, representing all capital and labour. Today we have the Council On Inclusive Capitalism representing all the “stakeholders.”

In Italy from 1925 to 1945, private employers remained, but were heavily regulated so that competition practically disappeared. This economic mechanism was carefully devised: strikes forbidden, the state arbitrating all disputes, and capital and labour represented by occupational syndicates, implementing guidelines set by the oligarchs through a framework that approximated the old guild system.

Does this begin to sound like socially-conscious environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria? Or former bank governor Mark Carney’s statement that corporations that fail to comply, will die?

“Firms that align their business models to the transition to a net zero world will be rewarded handsomely. Those that fail to adapt will cease to exist.” [5]

Spirit and mechanics

Fascism is state-corporatism, but the question of whether the business interest captures the state, or vice versa, depends on two different phases of fascism. Shaw called these the mechanics and the spirit.

The mechanics is how fascism operates. “True fascism must have a fascist economy since the purpose is to end the argument between capital and labour, replacing it with a united front.” The state will decide and apportion resources, using the strict application of codes and norms, subsidies and penalties.

The spirit of fascism is the application of the mechanics in the service of the owner class.

Shaw witnessed in real time the duel of two attempts to invert the capitalist model that had, until 20 years before, been the unchallenged, liberal “laissez-faire” for more than a century. He saw that this shift was not merely an economic evolution but a social revolution.

“In Europe the corporative state was the shield of big business; in the U.S. it hangs over the corporations and Wall St,” he writes.

There may be something to this. The Business Plot, as exposed by General Smedley Butler, was an alleged plan to stage a coup in 1934, overthrowing FDR. This is the opposition that Shaw identifies among the New York bankers and Pennsylvania industrialists. We cannot assume they were opposing FDR’s state-corporatism, for these included men who were financing Hitler.

In this power struggle, the owners in America were not, openly at least, following the same path as Italy and Germany. They were more confident in their economic and social hegemony. If they perceived their interest to be challenged, however, the fascist spirit would arise.

Who are the fascists?

America had its home-grown fascists: the Ku Klux Klan, the American Realists, the Silver Shirts, the Grayshirts, wrote Shaw, and “they are often anti-semitic and frequently roar out their belief in Nordic supremacy.”

“But these are not the true American fascists — the real fascists whom liberals view with alarm. Die-hard big business — the conservative bankers and industrialists and mine owners — with its constitutional slogans and financial power which could be used to raise and equip private armies if the need should arise: this is the spirit of fascism in America.

“These ‘fascists’ do not think of themselves as such, for fascism is foreign and fantastic, and these hard-headed executives are eminently practical men. In fact, they would consider the self-styled fascists of Smith or Blackburn almost as pestiferous as the equally fantastic American Marxists.

“The power of American big business to hire private armies — Pinkerton detectives, factory police, vigilantes, battling strike-breakers, etc — has been shown through the whole course of our industrial history. And it was with private ‘black’ and ‘brown’ armies, financed by big businesses, that Mussolini and Hitler and their industrial sponsors came into supreme power.”

If you want a narrative introduction to what Shaw describes here, read John Dos Passos’ “U.S.A. Trilogy.”

Today we again see a guild-like structure, backed by big business, seamlessly infiltrating every corner of corporate and public life — the same people, the same memberships, the same foundations, the same ideology.

The model is fascist, and it is already up and running.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Moneycircus to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.