Ukraine's Suffering Highlights Pulitzer Lies

The New York Times helped to cover up a genocide; as farming collapses once more

War in Ukraine and should prompt U.S. press corps to confront past lies

Walter Duranty won a Pulitzer Prize for praising Stalin while hiding famine

Moneyed interests and their intelligence arm used the press to manipulate policy

New York Times flattered Castro a decade before the CIA helped him to power\

U.S. State Department propagandized citizens long before Obama made it legal

(2,200 words or about 10 minutes’ read.)

May 17, 2022

For 90 years the U.S. media establishment has defended a man that Ukrainians regard as a criminal propagandist.

The New York Times journalist Walter Duranty covered up the starving to death of millions, flattered the dictator Josef Stalin, and was elevated to the heights of his profession, winning a Pulitzer prize.

“He is the personification of evil in journalism,” Ukrainian-American activist Oksana Piaseckyj has told an NPR reporter. “We think he was like the originator of fake news.” [1]

Duranty’s prize is the most controversial in Pulitzer’s history. Nevertheless when it was reviewed in 2003 the beadles left the award in place. Now one of the review panel, the NYT's former executive editor Bill Keller, favours pulling the Pulitzer.

What’s changed? — Ukraine is in the headlines. Famine, too.

Back in 2003 the NYT was still smarting from the lies about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and the plagiarism scandal of Jayson Blair.

Morality bends with the zeitgeist.

A brief history of starvation

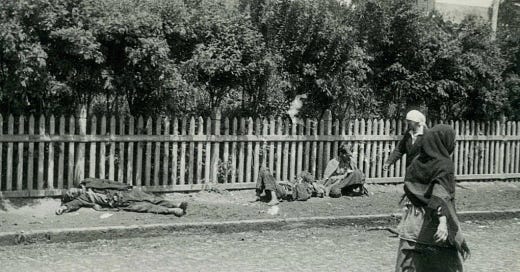

It wasn’t the first famine the Bolsheviks had caused. Within three years of seizing power the harvest of 1920 collapsed by half. By 1921 much of European Russia was in famine, lasting until 1923. Ten years later, the USSR was once again starving, the Ukraine worst hit.

The earlier famine was caused by civil war that lasted til 1923, the latter by the repression of skilled farmers, who were blamed for the disastrous failings of collective agriculture. In truth, they shared the same root.

When the Bosheviks took power, 97 per cent of the population lived in the countryside. The putschists controlled only the cities and held on to power by their fingernails. They needed control of the countryside. They declared war on the peasantry. [2]

Conventional histories say famine was an accident or unintended consequence. Event Covid should teach us better.

The Marxists’ postmodern heirs reverse the idea that ideology motivates the drive for power. Perhaps they are more honest than generations of Sovietophile academics. The American sociologist John Levi Martin argues that ideology is the “actors’ theorization of their own position, and available strategies, in a political field.”

The Bolshevik ideology of industrial progress insisted that centralized control of the economy could run things better, or at least give them power to designate the beneficiaries. Bureaucrats would follow the “imperatives” of technology.

This had less to do with Marxism-Leninism than people think. The Bolshevik leadership included hundreds of Russians, and especially Ukrainians, who had fled to the United States after the political violence of the 1880s. These progressives knew more about Frederick Taylor than Karl Marx.

Taylorism, or the theory of scientific management, including his time-and-motion studies, was cited often in the young Soviet Union. Aldous Huxley mimics this in Brave New World (1931) in which the god of religion is replaced by the deity of technological progress, with daily exclamations in praise of “Our Ford.”

This led to scientific absurdity of the Soviet bureaucrat Trofim Lysenko who believed he could teach wheat to grow in winter. He framed his ideas in Marxist terms to gain political protection and used this power to silence critics and send rival scientists to the GULAG. [3]

Lysenko’s victims were the early geneticists — in an eerie and ironic inversion.

Even worse than Lysenko are his apologists today. The Atlantic, a journal widely suspected to be close to the CIA, blames the resurgence in ideological views of science, and the beatification of Lysenko, on Russians — his victims. If you cannot see the dupicitous hand of “intelligence” or influence activities, I cannot help you. [4]

Ethnicity and accuracy

We are all humans and seek to apportion blame. We are also herd creatures and place blame outside the flock.

In the interests of strict accuracy, many of the architects of Bolshevism and the famine were Ukrainian, from the lands once known as Khazaria, and thus cross-networked to the Persian and Turkic peoples.

Meaning border land, Ukraine overlapped the borders of modern day Poland, giving us the “anarchists” who killed Tsar Alexander II which provoked the pogroms. They also gave birth to Trotsky, Radek, Khruschev and Kaganovich — these latter two were the supervisors, if not the architects, of the Holomodor, the name Ukraine gives to the politically-induced famine.

Ethnic name-calling doesn’t work. Nor does the game of playing one religion against another.

The Russian peasantry was deeply ritualistic, with life determined by observances and festivals, much of it pre-Christian Slavic folk culture overlaid with Orthodoxy.

They already practised cooperative farming. The short growing season in much of Russia makes common sense of collaboration, sharing tools and labour, as economist and former Russian finance minister Yevgeny Yasin has noted.

Yet in came the New York progressives yelling, “Wrong kind of collectivism!” The Bolsheviks appropriated what they could use from peasant culture — at one point they had children recite a daily prayer to Stalin — and liquidated the rest, or transported them to Siberia or the GULAG labour camps.

Duranty’s deception

This was the world in which Walter Duranty was appointed Moscow bureau chief of The New York Times for fourteen years (1922–1936).

Duranty wrote during the harvest of 1933: “any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda.”

That famine resulted in the death of between five and almost nine million people across the USSR, of whom four million were Ukrainian. A fellow Briton, Malcolm Muggeridge (Duranty was half British, half American) said in a 1982 documentary:

“He was not only the greatest liar among the journalists in Moscow, but he was the greatest liar of any journalist that I ever met in 50 years of journalism.”

Other journalists on the NYT knew the truth. New York had been a hotbed of revolutionary activism — Trotsky lived there in 1917, and departed for St Petersburg by ocean liner. The editors doubtless had connections among the 2.5 million Jews who had moved to New York from Russia and its regions. “Immigrant Jews felt a deep investment in a successful outcome to the Russian Revolution,” according to Tony Michels of University of Wisconsin.

“For days following the Tsar’s abdication on 15 Mar, 1917, mass meetings, balls, and grand concerts took place around New York city… an estimated 10,000-20,000 Jews attended a great ‘freedom demonstration’ in Madison Square Gardens, organised by the daily Forverts, the Socialist Party’s Jewish Federation, the U.S. office of the Bund (General Union of Jewish Workers in Lithuania, Poland and Russia) and the Russian Social Democratic Federation… Celebrants shouted themselves hoarse, for ‘the new government of the new Russia,’ reported The New York Times.” [5]

Was Duranty merely playing to popular sentiment and writing what his publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger (1891–1968) wanted to hear?

Sulzberger himself moved in the circles of oil magnates and bankers, many of whom helped fund the Bolsheviks, as the Stanford historian Antony Sutton revealed. Industrialists would continue their involvement over decades. These were not tycoons looking for short-term profit, however. The disruptive effect of the Soviet experiment was far too great for purely financial gain.

Agent of influence

Journalists have often worked with or for the intelligence agencies. Operation Mockingbird revealed the direct co-option of journalists by the Central Intelligence Agency. Event Covid and now war in Ukraine has revealed the pressure on news organisations to report in lock step, with a unified voice, in return for government advertising and subsidies.

Much of the broadcasting or news media today cannot be separated from government because of content and funding. This is well documented and will not be explored here. The Grayzone is an excellent source on Reuters and the BBC, for example. (Disclosure, the author worked as a producer at the BBC and a reporter at Reuters Television).

The media did operate, at one time, as an organic network, like a plant with roots comprising tens of thousands of local journalists who fed the trunk and stories like sap to the flowers, or stars, of the business. It was those myriad unseen roots that supplied not the headlines, but the self-knowledge that constitute the 97 per cent of news — the mirror in which society recognizes itself.

Nowadays it works in reverse like a funnel — no longer organic but mechanistic. News is poured by a handful of news agencies, Reuters, AFP, AP, Bloomberg, in the hand of the same investors — the bulk of outlets just copy and paste.

As an aside, information (bits and bytes) still flows upwards, but this consists of personal information generated on smart phones and computers, and increasingly tracked by our bank cards. This leads to the misconception of the hive mind; that knowledge is still flowing organically from the grass roots.

After the European Union created Rapid Response Units to unify government messaging, and the recent revelation by the Department of Homeland Security of its Disinformation Governance Board, knowledge (as opposed to information) is centrally-influenced if not controlled.

The online hate bills that have passed or are being legislated in Western countries strengthen this central control of knowledge, with censorship.

The question is not “where does The News come from” but whose interests it serves, and who pays for it to be disseminated.

Generally this means business, and a syndicate capable of organisation and unity. This is not new. Paul Reuter (born Israel Beer Josaphat) was in the oil business with the Rothschilds and was himself born of a banking family) before he set up the telegraphic news agency.

Castro: the CIA’s own boy

Leaving motive aside, the New York Times has form. The “journal of record” is also an agent of influence. It has the reach of a news agency such as Reuters or Associated Press. If you want to shape the narrative, it is where you place a story: it will get taken up everywhere.

The Times had lionised the young Fidel in April 1948, more than a decade before the Cuban Revolution. Castro led a student group financed by Argentina's Juan Perón, travelling to Bogotá, Colombia, afte the assassination of assassination of popular leftist leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Ayala - and to protest the founding of the rganization of American States.

The former U.S. ambassador to Cuba in the 1950s, Earl T Smith (1903-1991) explained how certain floors at the State Department “ran” Fidel Castro. The State Department withheld weapons from president Fulgencio Batista so that Castro’s Sierra Madre companeros could take over.

Smith told his interviewer Stanley Monteith (1929-2014) in the 1980s that while the CIA, through the State Department, pulled Castro’s strings, the NYT promoted him. In fact, the NYT made Castro famous as early as the 1940s when he was a mercenary in Bogota. [6]

Most of the media establishment continues to defend the Pulitzer. If they pulled Walter Duranty's prize, what would that say about The Guardian’s Carole Cadwalladr and Russiagate? According to special counsel John Durham’s investigation, Russiagate seems to have been a project of the FBI and Britain’s SIS/MI6 in league with the Clinton wing of the Democratic Party.

I have no idea who MI6 is working for. It simply is clear that it is not MI5’s watchword “Defend The Realm” There is a reason MI6’s motto is very different: Semper Occultus. (Disclosure: the author’s mother was secretary to Peter Wright, principal scientific officer for MI5 and author of Spycatcher (1987). [7]

Small world

For once we can agree with the Fakt Cheka at Associated Press: “Obama did not sign a law allowing propaganda in the U.S.” [8]

“The change essentially eased restrictions for Americans who want to access government-funded media content, allowing media produced by the U.S. Agency for Global Media, such as the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, to be made available to Americans “upon request.” That was not possible before the law was changed.

There was essentially a de facto ban on the domestic dissemination of materials originating from the State Department,” said Weston Sager, an attorney who published a paper on the change in law. “

Aw shucks. To think we couldn't read that wholesome, apple pie perspective that the U.S. government agencies were spreading abroad!

Yet “materials originating from the State Department” have been fed to the American population since forever, as we have seen in the case of the NYT’s young hero Fidel Castro.

One wonders how the repeal of Smith-Mundt could possibly have increased the propagandizing of the American public, given how they were already assailed from all sides.

The notion of influence cannot be separated today from propaganda. This is the doing of the biggest names in publishing and television. It is the state corporatist media that claims to be the trusted voice, and accuses others of mis-, dis- and mal-information (MDM) as the Council of Europe and others call it. [9]

Your response should be caveat emptor (consumer or recipient, beware). Yet even that is not enough. You must assume the intent to deceive. Corroborate everything you read on Moneycircus. Unlike the state corporatist press, we provide sources.

If the World Food Program's reports of impending famine are correct, I wonder how the NYT will report it this time around.

[1] NPR, May 8, 2022 — 'The New York Times' can't shake the cloud over a 90-year-old Pulitzer Prize

[2] Viola, Danilov, Ivnitskii & Kozlov, Yale, 2005 — The War Against the Peasantry, 1927-1930: The Tragedy of the Soviet Countryside

[3] The Irish Times, 2021 — West in danger of repeating Soviet ideological assault on science

[4] The Atlantic, 2017 — The Soviet Era's Deadliest Scientist Is Regaining Popularity in Russia

[5] Tony Michels, University of Wisconsin, 2017 — The Russian Revolution in New York, 1917-1919

[6] Stanley Monteith interview with Earl T Smith - The Fourth Floor: The Rise of Castro's Cuba

[7] The Grayzone, May 16, 2022 — Operation Surprise: leaked emails expose secret intelligence coup to install Boris Johnson

[8] AP, 2019 — Obama did not sign a law allowing propaganda in the U.S.

[9] Council of Europe, 2022 — Information Disorder